The Evolution of Cooling: Understanding F-gas and PFAS in Modern Refrigeration

Author: Georg Fösel, Refrigeration Specialist at MCI

Publishing date: 20/02/2024

Refrigerants are the blood in thermal energy systems – transferring thermal energy (i.e. heat) to different temperature levels by evaporation and condensation in the vapour compression refrigeration cycle; the basic process that is applied in refrigerators, air conditioning and heat pump equipment, process chillers, supermarkets, and reefers, among many other applications.

In the early days of refrigeration technology, any fluid that would undergo an evaporation and condensation process at achievable pressure and temperature levels where used. With more systems and applications in use, the number of accidents caused by machine defects or improper handling increased, paving the way for safe to use halogenated hydrocarbons, the Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Until the discovery of the ozone hole and the underlying root causes, these substances have been driving progress in food perseveration, health, and comfort control.

Please note that the landscape surrounding refrigerants, PFAS, and F-gas regulations is dynamic and subject to changes due to ongoing research, technological advancements, and shifts in environmental policies globally.

As such, while we create the article to the best of our knowledge in support of the industry and endeavor to keep the information up to date and correct at time of writing, we make no representations or warranties of any kind about the completeness or accuracy.

CFCs have been banned under the Montreal Protocol and the industry responded with replacement options such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). With lower (HCFC) to no (HFC) ozone depleting impact, efficient and safe operation was ensured, but they do contribute significantly to global warming when leaked to the atmosphere. At that time, leakage control, detection, and prevention were not a high focus of manufacturers, installers and owners of refrigeration equipment, which called for political action to regulate the use of these substances. With the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol in 2016, a global framework to lower the emission of HFCs was agreed upon and entered into national/regional legislation, such as the US American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act of 2020, the Chinese Management measures for fluorinated Greenhouse gases (Order No. 20) or the European Regulation (EU) No 517/2014.

The fading out of the PFAS area illustrates the uncertainty in the potential outcome of a restriction on refrigerants, defined as PFAS.

Understanding F-gases

Fluorinated greenhouse gases, often abbreviated F-gases or F-GHGs, are a group of substances defined in regulatory context as substances that contain fluorine, contribute to global warming and their use is being restricted.

While neither the Montreal Protocol nor the various Amendments, incl. the Kigali Amendment uses the expression, this international treaty regulates the use of certain substances, all listed in the various Annexes (A to F)1.

The European regulation that addresses F-gases (No. 517/2014) uses the expression “fluorinated greenhouse gas” to define the measures to control and phase down Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), Perfluorocarbons (PFCs), Sulphur Hexafluoride and other greenhouse gases that contain fluorine and are listed in Annex I of the regulation. For instance, R134a would be listed as “fluorinated gas”, whereas R1234yf which also contains fluorine is classified in the European legislation as “other fluorinated gas” – thereby being outside of the phase down schemes mandated by the regulation2.

F-gas regulations – Expand to read for each region

Europe

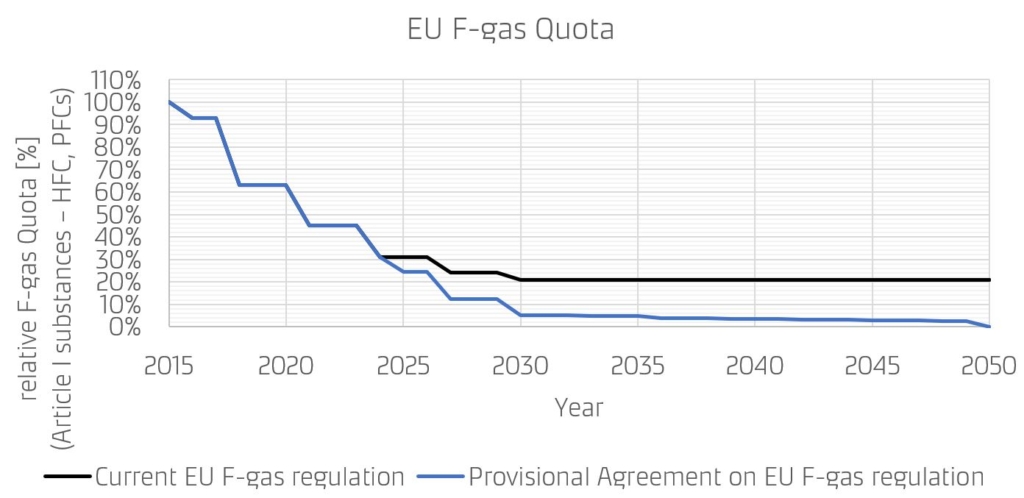

The latest developments at the end of 2023 and beginning of 2024 have been the reaching of a compromise between the three European institutions (Parliament, Council and Committee) on a revised F-gas regulation. The European parliament has approved this legislative resolution on January 16th 2024, with an overwhelming majority (457 (78%) in favour, 92 (16%) against, 32 (6%) abstentions). The adoption and entry into force is now just a formality, with the Council needing to formally endorse the text. 20 days after the publication in the EU Official Journal, the revised regulation will enter into force.

The key of the bill is the plan to phase out F-gases completely by 2050 in EU. This means that R134a and R513A will no longer be available, remaining solutions are HFO-refrigerants like R1234yf, Hydrocarbons like Propane (R290) as well as Ammonia (R717), Carbon Dioxide (R744) and Water (R718). These ambitions may be a blueprint for other regions to follow in a couple of years, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report (IPCC) has highlighted the need to lower emissions from fluorinated gases to 10% of 2015 levels. So, one could expect more significant phase-down or phase out schemes in other parts of the world in the near future.

HFCs will only be available as reclaimed and recycled substances, limiting the availability for service and calling for alternative solutions ahead of time to ensure equipment uptime.

Keeping in mind, that European regulations apply to machines manufactured, placed on the market, or used in Europe, the below regulations will also affect reefers serviced or placed permanently in Europe:

- Service ban using virgin refrigerants:

- Refrigerants with GWP >2500 from 2025 onwards = R404A, R452A.Refrigerants with GWP >750 (except military equipment or for applications below -50°C) from 2032 onwards = R134a.

- Mandatory leak checks, every year.

- Mandatory refreshment training for F-gas handling certified technicians, at least every 7 years.

- Penalties for infringement to regulation, below are max. fines:

- 5 x market value of used gas/products/equipment.

- For repeated infringement within 5-years, penalties increase to 8 x market value of used gas/products/equipment.

- Review and potential tightening of measures in 2030 and 2040 (Article 35).

All these measures will require more attention on the service chain to be compliant with the legislation.

On a side note, the F-gas regulation defines a new foundation to calculate the global warming potential of refrigerants in Europe:

- GWP values are calculated as below, to ensure coherence with the obligations under the Montreal Protocol

- HFCs and mixtures of these, like R134a shall be based on the 4th Assessment Report of the IPCCOther fluorinated gases, e.g. HFOs like R1234yf, shall be based on the 6th Assessment Report of the IPCC.R134a → 4th IPCC AR → GWP=1430R1234yf → 6th IPCC AR → GWP=0.5

- R513A → 56% R1234yf + 44% R134a → 56%*0.5+44%*1430 = 629.48

USA

Fluorinated gases are also on the attention of US policy, the framework to control these substances and response to the actions required from the Kigali Amendment is the final rule of the Phasedown of Hydrofluorocarbons: Restrictions on the Use of Certain Hydrofluorocarbons Under the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2020 (AIM Act), which became effective on 26.12.2023.

The AIM Act regulates the phasedown of the F-gases by phase down of production and consumption through an allowance allocation program and enforcing transition to next generation technologies, under consideration of the particularities of the industrial sectors.

The phase down is well on the way, with a 10% reduction of allowances from 2022 and a 40% reduction from 2024, compared to the baseline values established.

The sector-based transition to next-generation technologies ensures that refrigerants, foams, aerosols, and other substances with high global warming potential are replaced with lower GWP alternatives wherever feasible. This practice of setting application specific GWP limits has worked well in Europe, ensuring transition of technology to more environmentally friendly alternatives. One example of the US application based GWP limits is a level of 700 or below for refrigerants used in intermodal containers, when operating above -50°C. The final rule clarifies that reefers used to transport good into and out from the United States (“are actively in use when travelling into U.S. jurisdiction from shipments of used products destined for resale or further distribution”) and only reefers sold in the United States need to comply with the HFC limitations[1]. But for reefers used domestically, this means a transition from R134a to R513A as a minimum.

[1] In the final rule, US EPA addresses the concerns raised by the industry, that this rule does not apply to Intermodal Containers transporting goods into the US:

Comment: Other commenters asked that EPA clarify how the import restriction applies to existing intermodal containers that are engaged in trade, refrigeration equipment in operation on ocean-going vessels, and non-road motor vehicles temporarily deployed overseas. Commenters stated that applying the GWP limit to all refrigerated containers is infeasible and would be highly disruptive to trade. Commenters also stated that such equipment should be allowed to be serviced in the United States and not be subject to the recordkeeping and reporting requirements.

Response: EPA agrees that applying the restrictions to products that are actively in use when travelling into U.S. jurisdiction could be problematic. For example, a strict reading of the proposed restrictions on import could have prevented a traveller from re-entering the United States from Canada or Mexico with their car if the MVAC uses HFC–134a. As noted in the proposed rule, the Agency’s intention is to cover the activities of entities bringing large shipments of products into the country, as well as activities of entities bringing smaller volumes of products into the country (e.g., driving a truckload of air conditioning units across the Canadian or Mexican border for sale in the United States.). EPA therefore is distinguishing in this final rule those products or systems that are actively in use when travelling into U.S. jurisdiction from shipments of used products destined for resale or further distribution. EPA is not intending that this aspect of this rule restrict RACHP equipment in operation aboard marine vessels, planes, motor vehicles, refrigerated transport trailers, or intermodal containers. Likewise, foam or aerosol products that are in use (e.g., trailers) or in possession of a consumer when crossing the border are likewise exempt from the import prohibition. However, EPA’s intent is to apply the use restrictions consistently for domestic manufacturers and importers of products. As such, no person may sell new refrigerated transport trailers or refrigerated intermodal containers in the United States, whether manufactured domestically or abroad after the manufacture/import compliance date, unless it complies with the HFC use restrictions.

[1] In the final rule, US EPA addresses the concerns raised by the industry, that this rule does not apply to Intermodal Containers transporting goods into the US: Federal Register :: Phasedown of Hydrofluorocarbons: Restrictions on the Use of Certain Hydrofluorocarbons Under the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2020:

Comment: Other commenters asked that EPA clarify how the import restriction applies to existing intermodal containers that are engaged in trade, refrigeration equipment in operation on ocean-going vessels, and non-road motor vehicles temporarily deployed overseas. Commenters stated that applying the GWP limit to all refrigerated containers is infeasible and would be highly disruptive to trade. Commenters also stated that such equipment should be allowed to be serviced in the United States and not be subject to the recordkeeping and reporting requirements.

Response: EPA agrees that applying the restrictions to products that are actively in use when travelling into U.S. jurisdiction could be problematic. For example, a strict reading of the proposed restrictions on import could have prevented a traveller from re-entering the United States from Canada or Mexico with their car if the MVAC uses HFC–134a. As noted in the proposed rule, the Agency’s intention is to cover the activities of entities bringing large shipments of products into the country, as well as activities of entities bringing smaller volumes of products into the country (e.g., driving a truckload of air conditioning units across the Canadian or Mexican border for sale in the United States.). EPA therefore is distinguishing in this final rule those products or systems that are actively in use when travelling into U.S. jurisdiction from shipments of used products destined for resale or further distribution. EPA is not intending that this aspect of this rule restrict RACHP equipment in operation aboard marine vessels, planes, motor vehicles, refrigerated transport trailers, or intermodal containers. Likewise, foam or aerosol products that are in use (e.g., trailers) or in possession of a consumer when crossing the border are likewise exempt from the import prohibition. However, EPA’s intent is to apply the use restrictions consistently for domestic manufacturers and importers of products. As such, no person may sell new refrigerated transport trailers or refrigerated intermodal containers in the United States, whether manufactured domestically or abroad after the manufacture/import compliance date, unless it complies with the HFC use restrictions.

As with the European Union’s F-gas regulation, so does US EPA’s GWP values not strictly follow the latest IPCC reports, but lists below values lists GWP for substances and the references:

- R134a: 1430 (4th AR IPCC) = same as EU

- R1234yf: 1 (WMO 2022) -> different to EU

- R513A: 630 (Calculated) -> different to EU.

China

China, as defined in the Montreal Protocol as a developing country, has not yet started with the reduction of HFC gases, as Europe, the United States, and other developed countries. But as of 2024, a freeze of production and use of HFCs at the baseline level has been implemented (the baseline is the average value of HFCs from 2020 to 2022 plus 65% of the baseline level of hydrochlorofluorocarbons, calculated in units of carbon dioxide equivalent). This level is reduced by 10% from 2029 onwards and will aim an 80% reduction from 2045, unless more stringent regulations are implemented, following the example of the European Union.

Understanding PFAS

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) revised the definition of PFAS in 2021, stating that:

“PFASs are defined as fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I atom attached to it), i.e. with a few noted exceptions, any chemical with at least a perfluorinated methyl group (–CF3) or a perfluorinated methylene group (–CF2–) is a PFAS.

The rationale behind the revision is to have a general PFAS definition that is coherent and consistent across compounds from the chemical structure point of view and is easily implementable for distinguishing between PFASs and non-PFASs, also by non-experts. The decision to broaden the definition compared to Buck et al. is not connected to decisions on how PFASs should be grouped in regulatory and voluntary actions.”

Refrigerants and their atmospheric decomposition products, Plastic materials such as PTFE and many more are falling under the OECD definition, some estimate that more than 12,000 substances would be classified as PFAS.

PFAS regulations – Expand to read for each region

Europe

The environmental agencies of Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark submitted a restriction proposal addressing PFAS to the European Chemical Agency (ECHA). They argue, that PFASs are, or ultimately transform into, persistent substances, leading to irreversible environmental exposure and accumulation. Due to their water solubility and mobility, contamination of surface, ground and drinking water and soil has occurred in the EU as well as globally and will continue. Removal of PFAS is difficult and costly when released to the environment. In addition, some PFASs have been documented as toxic and/or bio accumulative substances, both with respect to human health as well as the environment. Without acting, their concentrations will continue to increase, and their toxic and polluting effects will be difficult to reverse.

The proposal is the “broadest restriction proposal in history” to avoid regrettable substitutions by other PFAS.

The restriction proposal is in the opinion development phase of the Risk Assessment Committee (RAC) and Socio-Economic Analysis Committee (SEAC). In a commenting period, more than 5600 comments have been submitted – containing more than 100 000 pages of information. This “record number of comments“ [Maria Ottati, Chair of SEAC], which is much more than for other restriction proposals, poses a problem on the anticipated timeline of the review process. The next steps in the ECHA restriction proposal is to discuss the use-sectors, which have received the least number of comments, such as cosmetic products, ski wax and other consumer mixtures, as these can be timely assessed. The ECHA is currently discussing a joint plan on how to best evaluate the proposal with the five submitting national authorities (Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark).

In the meantime, the “Forum for exchange of Information on Enforcement” published their advice on the enforceability of the restriction proposal. The report lists the following issues:

- Lack of clear substance identification

- PFAS is defined by structure, not by CAS number or alike, making it a challenge to control this by enforcement authorities.

- Unclear applicability of restriction of substances

- As an example, it is unclear, if the about of PFAS in a coating or on a whole product needs to be considered in terms of maximum concentration (25 ppb – 50 ppm).

- Overlapping with existing legislation

- It is not straightforward what legislation (e.g. F-gas regulation) is the strictest and shall be followed. This will create non-harmonized interpretations on the applicable rules.

- Lack of standardized analytical processes

- Only approx. 100 PFA substances can be determined with the proposed methods = 1% of the 10 000 PFAS aimed to be restricted.

In summary, the proposal is found to be costly, unpractical and challenging to enforce by the Enforcement Advisory Board.

USA

The Environmental Protection Agency focuses their attention and restriction work on long-chained PFAS (6 or more carbon atoms). In their National PFAS Testing Strategy the EPA uses the same definition of PFAS from OECD as a starting point, but focuses on PFAS of concern based on their persistence and potential for presence in the environment and human exposure. EPA notes, that for example, chemicals with (-CF2-) that are not (-CF3) are expected to degrade in the environment and most substances with only one terminal carbon (-CF3) are expected to degrade to trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), which is a well-studied non-PFAS. Chemicals with such degradation potential and for which vapor pressure could not be calculated were also excluded from the starting list.

Refrigerants, like R134a, R513A or R1234yf have medium to short atmospheric lifetime and degrade to various degree to TFA.

China

China follows the US in focusing on restricting longer chained molecules of the PFAS group of substances, such as (6-8 carbons). Short chained PFAS molecules, like TFA are not excluded as done by US EPA but are also not in the focus as in EU ECHA proposed regulation.

Summary and Conclusion

Refrigerants are the vital component in a refrigeration system to lower and control temperature for food, pharmaceuticals, maintain comfort by heating and cooling and are therefore essential for modern societies. Environmental concerns have led to restriction of use, and it is likely that these will be tightened in the future. To maintain these benefits for society, while reducing the environmental impact as much as possible, it is important to:

1.) Design energy efficient refrigeration systems, as fossil fuels are still the main source of energy to power these systems. This entails also reducing the need for refrigeration to the least possible extent, e.g. by improved and more durable insulation. The selection of refrigerant and foaming agents plays a key role.

2.) Design robust refrigeration systems that maintain their energy efficiency over their lifetime. Any premature retired machinery adds to the environmental footprint through its production carbon footprint.

3.) Operate refrigeration systems with care, e.g. avoiding excessive use of chemicals for cleaning, that could negatively impact the health of refrigeration systems.

4.) Monitor refrigeration system performance in order to act swiftly on malfunctioning/suboptimal performing machinery.

5.) Service and maintain refrigeration systems, ensuring proper refrigerant management to avoid leakages to the absolute minimum and detect potential leaks as early as possible.

6.) Ensure proper end-of-life management of equipment, including recovery and recycling of refrigerants.

Maersk Container Industry is committed to impact all of the above items, through continuous research on refrigeration technology, including refrigerants, improving product reliability and longevity, developing digital solutions that monitor equipment continuously during operation, as well as providing training and service solutions.

Links

1) Information on the Montreal Protocol, Adjustments and Amendments

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer | Ozone Secretariat (unep.org)

2) Current EU F-gas regulation

3) US legislation to phase down HFCs:

4) US GWP values

Technology Transitions GWP Reference Table | US EPA

5) Information on EU PFAS restriction proposals (Proposal, comments, enforceability)

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – ECHA (europa.eu)

6) Information on US EPA’s actions on PFAS